Recognition

1996 AIGA Medal

Born

1931, Bronx, New York

Deceased

November 18, 2022

By Andrea Codrington Lippke

October 1, 1996

In today's market research-driven advertising industry, visceral instinct has all but been replaced by irony, the stark effect of image and text by a sly, focus group-inspired wink. Ask legendary New York adman George Lois what he thinks of this, and step out of the way. “Advertising is not a fucking science,” he roars, “advertising is an art—no questions about it.” And Lois should know. As one of this century's most accomplished progenitors of Big Idea advertising, the 66 year-old ad luminary has given birth to an astonishing array of commercial campaigns and imagery that have meshed high-minded design with hard-core sell. “Great ideas can't be tested,” emphasizes Lois. “Only mediocre ideas can be tested.”

So impassioned by his work is Lois that it is difficult to imagine the hulking adman—his athletic, 6'3" frame only slightly diminished by his years—at rest. “I sleep three and a half hours in two shifts,” he confesses. “I think it's part work ethic and part craziness.” Whether such perpetual motion is the product of metabolism or habit is difficult to ascertain. After all, Lois was born in 1931 into a family of hard-working, early-rising Greek immigrants who spent their days and nights making their way in the rough Kingsbridge section of the Bronx. Working with his florist father from the time he was five years old, Lois was witness to long hours and backbreaking labor. The image of his father's fingers tattooed with cuts and scratches has left an indelible mark. Lois's hands may be smooth, but as he drums his fingers across the table or pounds a fist for dramatic emphasis, his opinion comes though loud and clear. “If you don't burn out by the end of each day,” he maintains, “you're a bum.”

It is easy to picture the young George Lois fighting his way through the all-Irish neighborhood on his way to school. An exquisitely crooked nose and a jolting propensity for wedging an emphatic “Yo!” into the middle of a sentence are testament to the street kid within. And Lois had a lot to fight about. There was the matter of ethnicity, of course. And then there was the art thing. “I was so involved with drawing all the time,” Lois says. “I remember sitting in my fire escape and drawing converging lines when I was six or seven years old. I would draw 3-D lettering on everything.” While the young Lois was defending his besieged masculinity, his public school teacher Ida Engle was collecting the hundreds of drawings that he had produced over the years: a portfolio that gained him entrance into the prestigious High School of Music and Art.

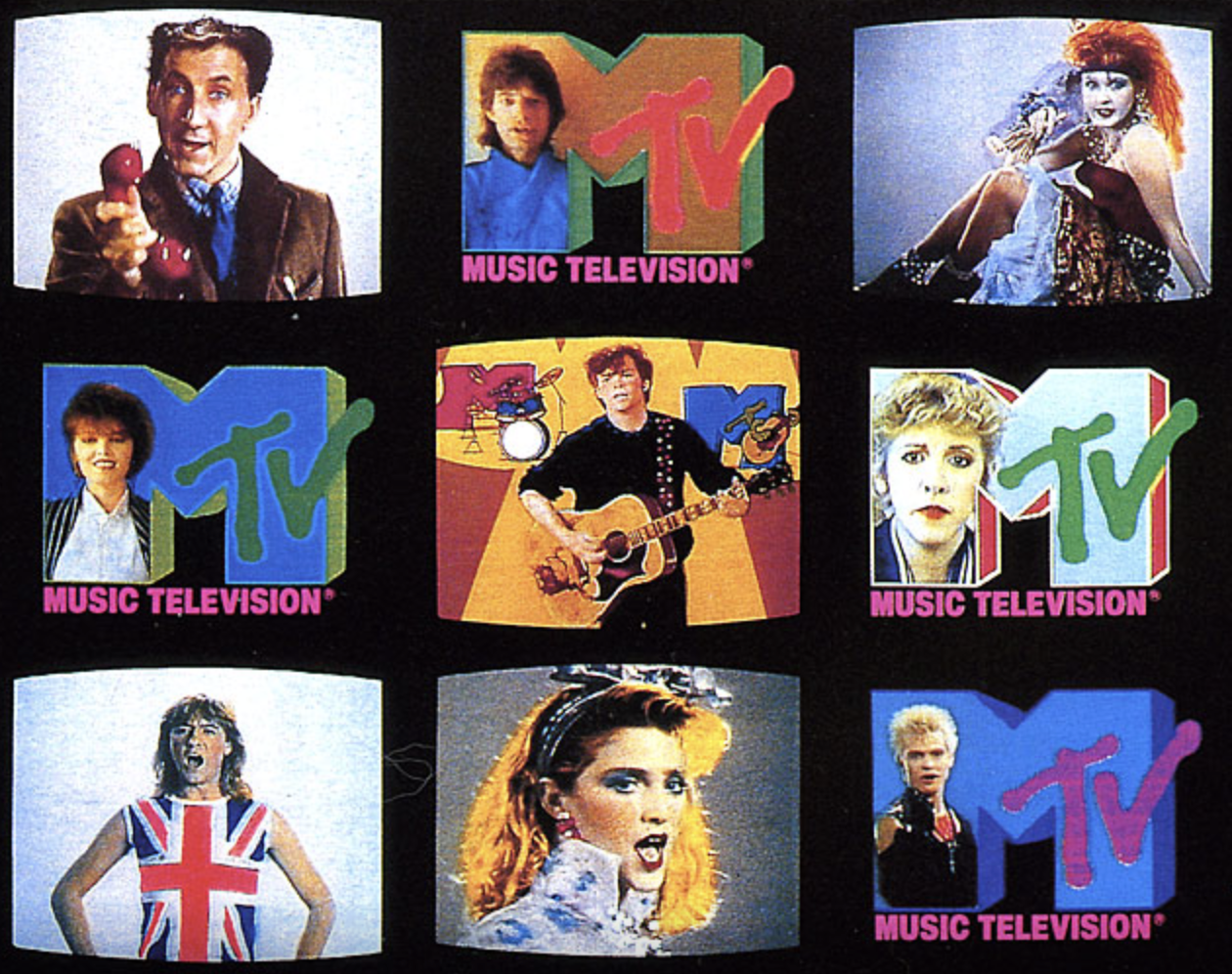

Panels from the famed I Want My MTV campaign that persuaded cable operators to carry MTV, 1982.

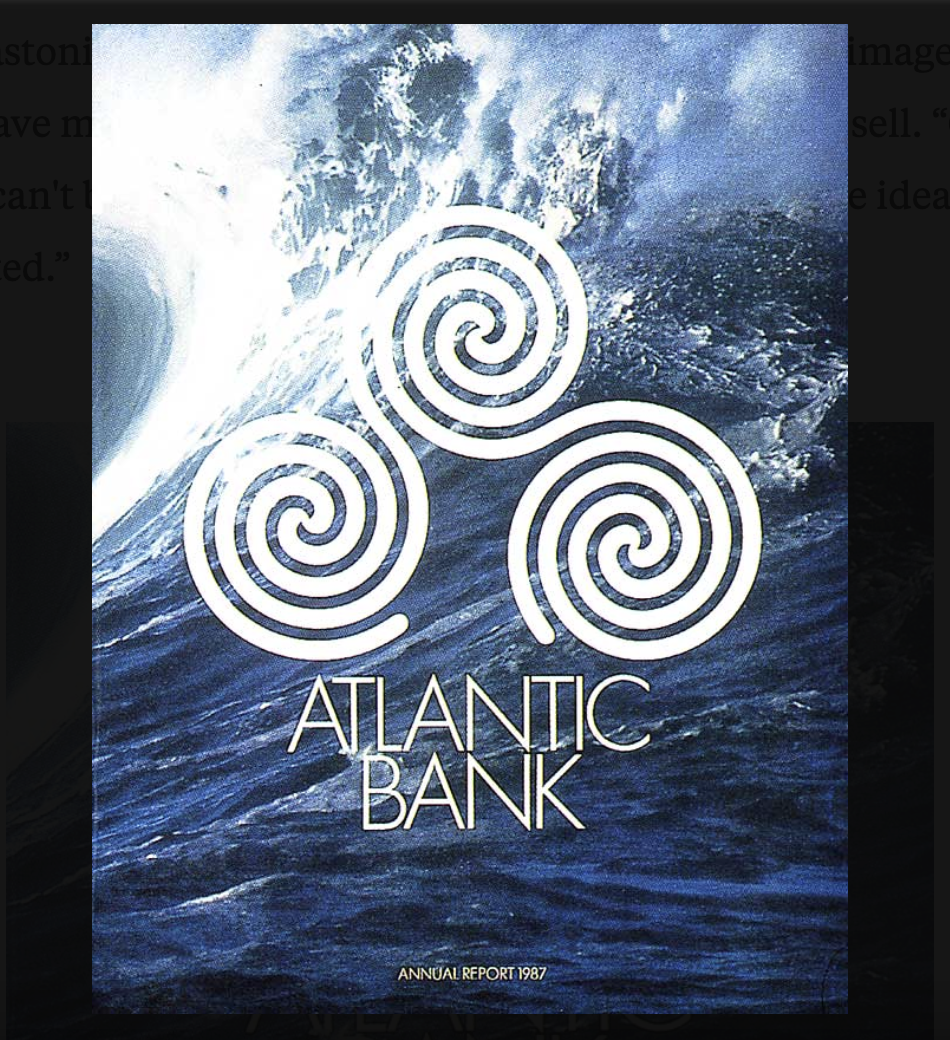

Logo (on an annual report) for a Greek bank in the U.S. that specializes in shipping.

Photograph of Fred Ota, Tom Miller, John Weber, 1953. Thomas H. E. Miller Design Papers, Special Collections and Archives, University of Illinois at Chicago.

“I always knew I was the most talented kid in the school, ” says Lois of his time at Music and Art. “I also knew I was a lucky son of a bitch to be there.” Exposed to the city's best art education, not mention school concerts directed by the likes of “a young Lennie Bernstein and Maestro Toscanini,” Lois thrived in the Bauhaus-based atmosphere and impressed his instructors, who for the most part were able to see the diamond of his talent in his street-rough demeanor. But not everybody appreciated—or understood—Lois's emerging conceptual sensibilities. A sophomore-year incident in which hi class was given a sheet of paper to design “yet another Bauhaus rectangle composition” almost led to his being flunked. “I sat there and didn't move with this 18 by 24 sheet in front of me for an hour and a half,” laughs Lois. “The teacher was getting furious. At the end, she went to grab my blank paper and I held up my hand to stop her. I signed my name to it and said, 'Here's the ultimate rectangle design.' The teacher just didn't get it.”

Despite such scrapes with authority, Lois made it though Music and Art and came out the other end with a diploma, a basketball scholarship to Syracuse, and an acceptance to Pratt. “One-third of my life is playing basketball,” confesses Lois, who nonetheless chose to go to Pratt for its proximity to home and its reputable commercial arts program. “I was the wild man of the class,” Lois recalls of his first year at Pratt, whose foundation course was old new to the Music and Art graduate. Rather than concentrate on his schoolwork, Lois set himself to winning over a beautiful blonde classmate (he did, despite her initial reaction of “Me Rosemary, you arrogant”) and impressing advertising professor Herschel Levit. Life began in earnest Lois's sophomore year, when he decided, at Levit's urging, to leave Pratt for a job in the design studio of Reba Sochis and eloped to Baltimore with his Polish Catholic bride.

Lois adored Sochis—a great designer and a great curser, it turns out—but spent only a short time working with her. Having left college, he became subject to the draft and got nailed for a two-year Army stint, landing in the thick of the Korean War. When he returned in 1953, Sochis was eager to make him a partner in her studio, but Lois wanted to go out into the world. William Golden's renowned advertising and promotions department at CBS was Lois's next port of call, where the experience-hungry Lois designed booklets, mailers, letterheads, theatre marquees, program notices and ads and was further exposed to the work of such design and illustration Masters of the Universe as Ben Shahn, Kurt Weihs and Lou Dorfsman.

“People who don't think they owe something to somebody are crazy,” says Lois with emphatic gratitude. The list of creative giants who inspired and facilitated his own creative vision is lengthy, and he is the first to proclaim this. After leaving CBS and taking on short, stormy stints at the ad agencies Lennen & Newell and Sudler & Hennessy—where he hooked up with another design legend, Herb Lubalin—in 1959 Lois landed at Doyle Dane Bernbach, the agency that gave birth to Big Idea Thinking, the basis of truly modern advertising. “I always understood concept,” says Lois, who felt at home at DDB, where the art director was king. Combining shrewdly shot visuals with irreverent text, Lois and his colleagues came up with such seminal advertising moments as the Volkswagen ”Think Small“ campaign. “Everything I did was looking for the Big Idea,” recalls Lois, “but you're not going to get to an idea thinking visually in most cases. You have to think in words, then add the visual. Then you can make one plus one equal three.”

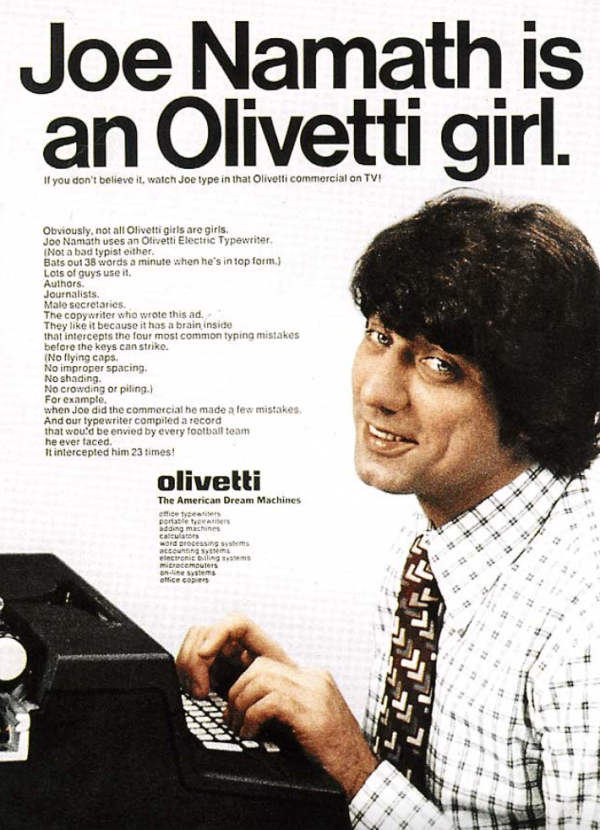

Joe Namath as an Olivetti girl (Lois's response to criticisms of sexism in previous Olivetti ads, 1967.

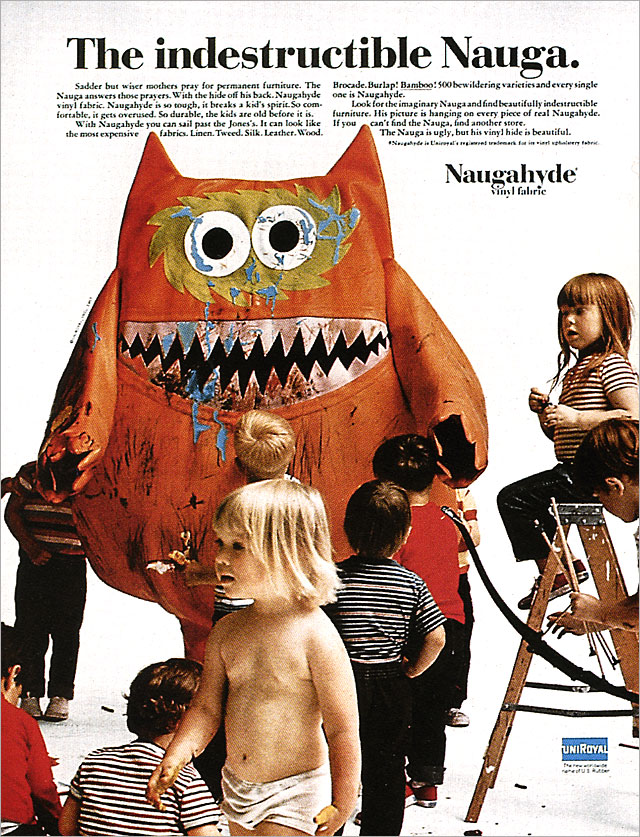

Ad featuring the Nauga, a mythical beast created to brand Naugahyde, 1966.

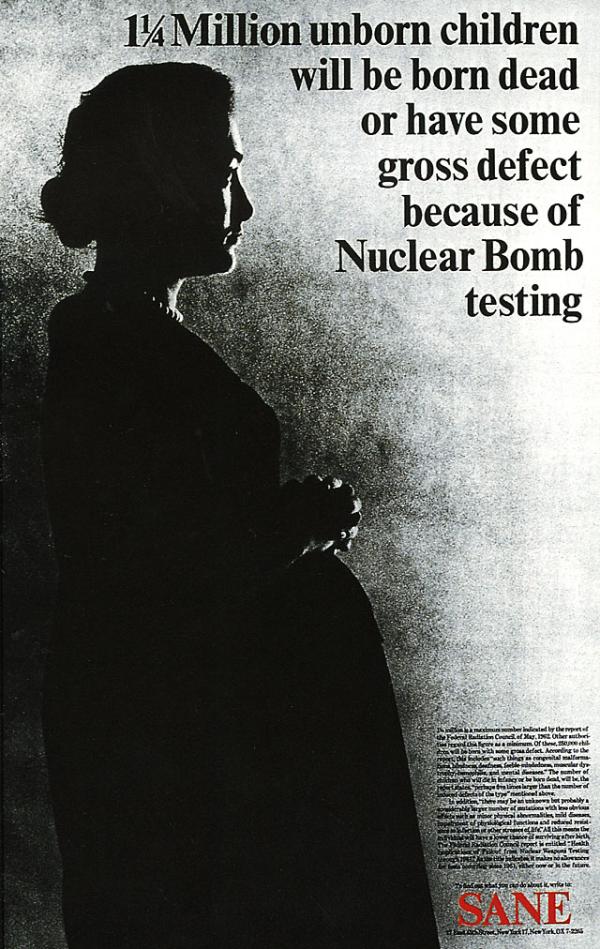

Controversial anti-nuclear poster created for the organization SANE, 1963.

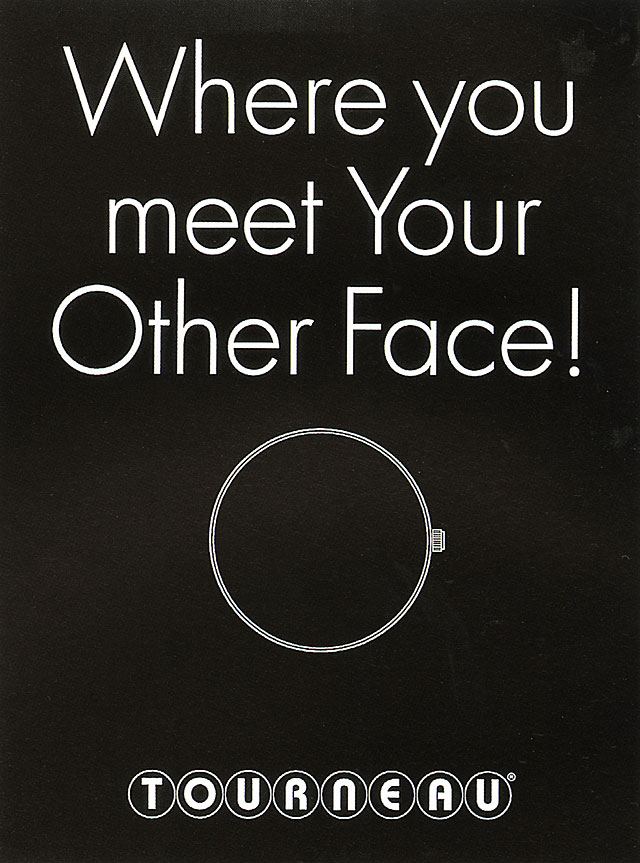

Tourneau Swiss Watches ad, 1997.

Louis's powerful individualism and unconventional antics—hanging out the window yelling at a client, “You make the matzoth, I'll make the ads,” to name one instance—made it inevitable for him to leave DDB in 1960 to open up his own agency, Paper Koenig Lois. Unconstrained by convention and static corporate hierarchies, PKL soon became the world's hottest agency, creating memorable campaigns for everything from gourmet pickled Dilly Beans and Xerox to Aunt Jemima and National Airlines. But Lois has always been given to remaking himself and his business: since 1967, he has created three wildly successful agencies—Lois Holland Callaway, Creamer Lois and Lois Pitts Gershon, which is now his present agency, Lois/EJL.

Throughout his career, Lois's talent has always been to capture the zeitgeist of an age—whether in the form of a senatorial campaign for Bobby Kennedy (1964), a composited Esquire cover that has Andy Warhol drowning in an oversized can of Campbell's soup (1969), the concept and name for the low-calorie Stouffer's product Lean Cuisine (1979), or those entertainment industry-transforming words, “I want my MTV” (1982).

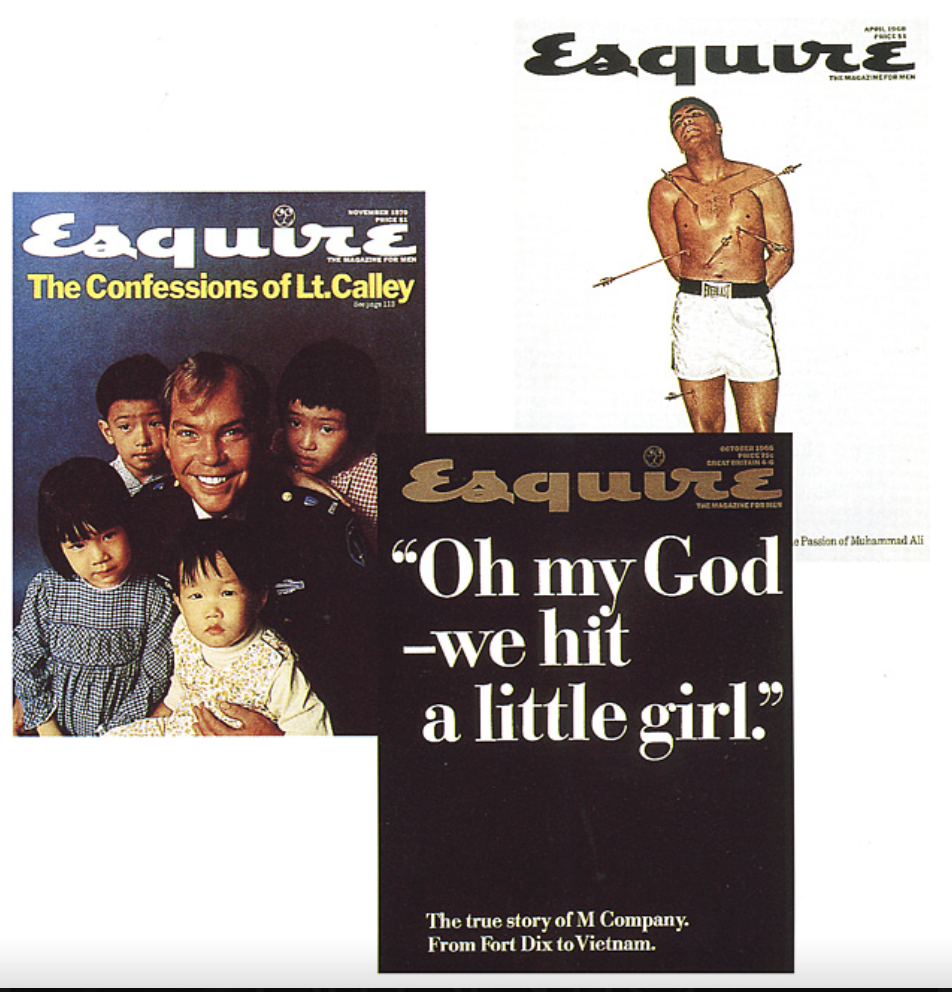

“I'm the crossover guy,” says Lois of his career, which has borrowed as much from graphic design as it has from guerilla advertising tactics. Lois laughs when he remembers his advertising colleagues' reaction when seeing him cut his type apart at his desk with all the earnest intensity of a Bauhas student. “'Geez,' they'd say, 'He's a real dee-signer.' I took that kind of design sensibility and put it together with a kind of kick-ass sensibility and made my own kind of advertising.” The most memorable manifestation of this hybrid talent undoubtedly came in the form of the covers he created for Esquire in the '60s and early '70s. Blessed with the partnership of editor Harold Hayes, who allowed the art director creative control, Lois gave this particularly vibrant and turbulent era a memorable face: Muhammad Ali as the Christian martyr St. Sebastian; Svetlana Stalin with a drawn-on mustache; mean-assed boxer Sonny Liston as the first-ever African American Santa Claus. And an all-black cover punctuated only by reversed-out type reading “Oh my God—we hit a little girl,” Lois's stark commentary on a war that was anything but black and white.

Lois has come far with his visceral approach to art direction. (An appearance on the David Suskind show many years ago had him claiming: “Advertising is poison gas. It should absolutely attack you; it should rip your lungs out!”) Stripping aside all hyperbole, however, George Lois is able to appreciate the more subtle indicators of his life-long success. Lois may have made his fortune, been inducted into the Art Director's Club Hall of Fame, the Creative Hall of Fame and been awarded the AIGA Gold Medal. But nothing compares to a phone conversation he had a few years ago with his beloved pal, the late Paul Rand. Lois's full lips form a tender smile as he remembers Rand saying, “You son of a bitch, did you see the Times this morning? You were an answer in the crossword puzzle!”

Copyright 1998 by The American Institute of Graphic Arts.