Given one minute to make a provocative presentation about design at the 2005 AIGA National Design Conference, 20 designers took the stage, encumbered with elaborate animations, PowerPoint presentations, professional-grade films. Michael Bierut appeared in a suit, strolled to center stage, and performed a self-penned AIGA version of “The Star Spangled Banner.” A capella.

It was the vocal equivalent of Bierut's work: smart, bold, blissfully on target. He received a standing ovation.

The fact that Michael Bierut will stand on stage and sing before almost 3,000 designers is not surprising—Bierut has built his career on making himself, his work, his personality, his opinions, available. It has worked to great effect. He graciously jets to speaking engagements tucked into tiny towns in corners of the country. He makes a point to advise design students. But this should be of no surprise. After all, Michael Bierut is a Midwestern-raised, impeccably-mannered person-who happens to be one of the most famous graphic designers today.

Bierut was born in Cleveland, Ohio in 1957. Graphic design as a career aspiration was not heavily promoted to the young adults of Ohio at the time. Yet his loves of fine art, music and drawing—all converging, to him, in the form of album covers—eventually led Bierut to what were apparently the only two graphic design books in his suburban town's branch library: the Graphic Design Manual by Armin Hofmann and Milton Glaser: Graphic Design. He needed little more to convince him to study graphic design at the University of Cincinnati's College of Design, Architecture, Art and Planning. An internship while in school placed him under the guise of another AIGA Medalist, Chris Pullman, at Boston public television station, WGBH.

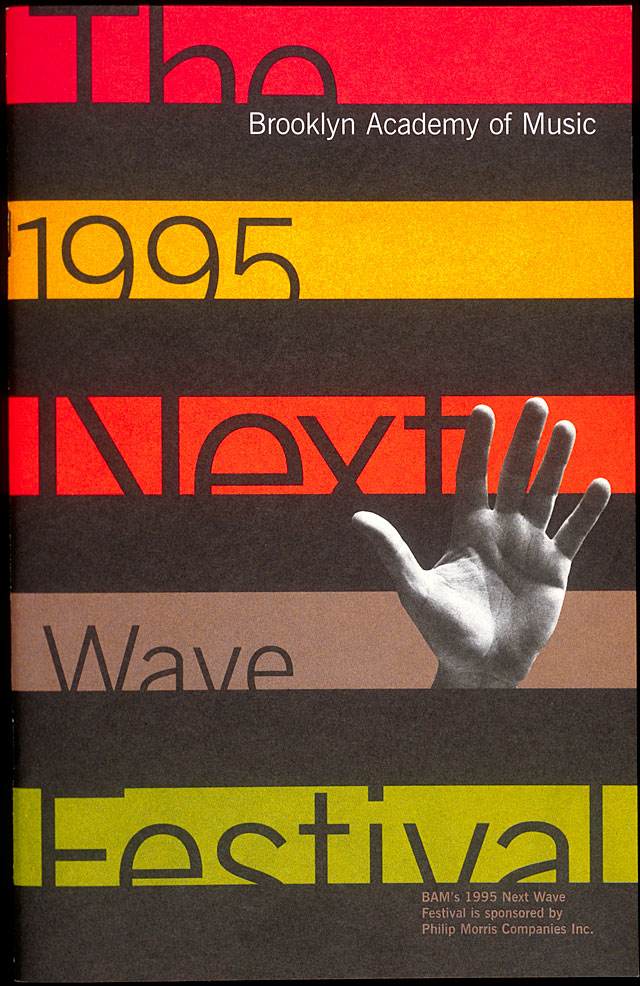

Brooklyn Academy of Music (BAM) identity (1995).

Alliance for Downtown New York Streetscape signage for Lower Manhattan (2001).

Good Diner identity (1992).

In 1980 Bierut landed his first job at one of the most important design firms in the world, working for Massimo and Lella Vignelli in New York City. Working alongside legends for 10 years at Vignelli Associates, eventually as vice president of design, gave Bierut serious industry clout. But it also instilled a keystone tenet of his career. “Probably the most interesting thing I learned is that a lot of the things about design that tend to get designers really interested aren't that important,” Bierut once said to Steven Heller. Bierut has admitted that there's no proof people ever really read the annual reports and corporate brochures that designers make. Therefore, Bierut strives to not only make things that people are able to read, he makes people want to read them. “He has a quality that I have much respect for in the kind of work that we do,” says Pullman. “He's a person who's very easy to understand, both when you talk to him and when he's doing his work. He's accessible, humane, funny when it's appropriate, and witty almost all of the time. And that's a very important quality for someone who wants to be a communicator.”

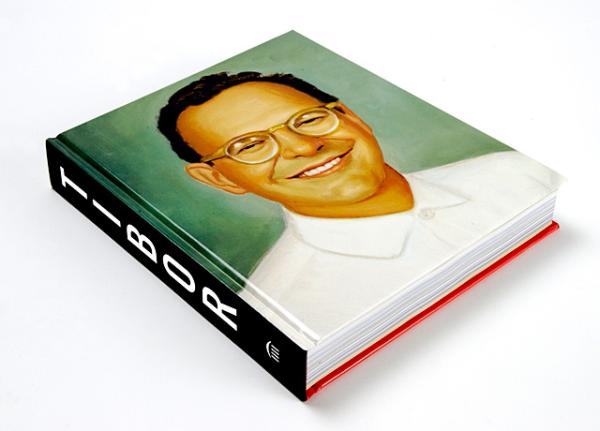

It is this “democratization of design” that Bierut has championed while a partner at Pentagram, where he's been since 1990; the act of making things digestible is where he excels. His list of clients consists of massive corporations that need to be embraced by the masses: Walt Disney, United Airlines, Motorola, the New York Jets, the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. Or he lends a voice to complex, intellectual entities that need emotional authenticity: Yale and Princeton Universities, Brooklyn Academy of Music, New York magazine. This aesthetic also informs his work as an author, co-editing the design essay series of Looking Closer and co-writing and designing the monograph Tibor Kalman, Perverse Optimist.

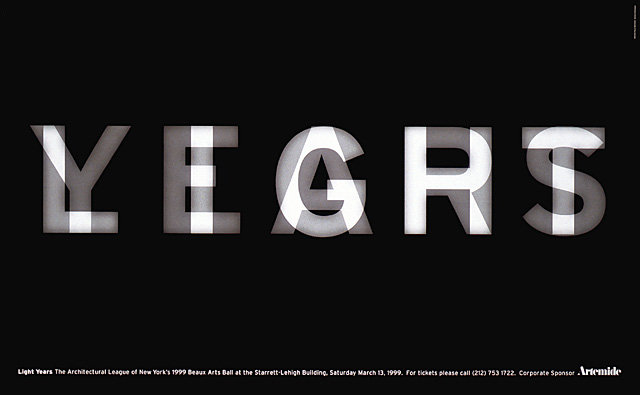

Like Kalman, Bierut has not only made a profound mark on design, but embedded himself in the cultural concrete of New York City. Bierut is a director of the Architectural League of New York and a member of New Yorkers for Parks. He created wayfinding signage for the Alliance for Downtown New York, assisting millions of tourists navigating the streets of Lower Manhattan. Bierut's pieces can be seen at two New York museums, the Museum of Modern Art and the Cooper-Hewitt, National Design Museum, and more around the world. It was also in New York that he became involved with AIGA, initially drawn into the fold when asked to DJ chapter events. Bierut was president of AIGA's AIGA's New York chapter from 1988 to 1990 and president of AIGA from 1998 to 2001; he has since been named to the Art Directors Hall of Fame and the Alliance Graphique Internationale.

United Airlines identity consultancy (1997-present).

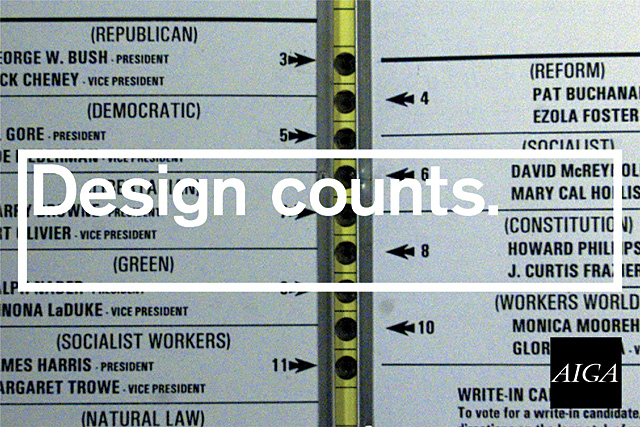

AIGA National Design Conference Design Counts poster (2001)

Book design for Tibor Kalman: Perverse Optimist published by Booth-Clibborn Editions/Princeton Architectural Press (1998).

The Architectural League of New York Light Years poster (1999).

But Bierut's influence swings far beyond design circles—so far, in fact, that he is one of the very few people the mainstream media turns to for design commentary. He's appeared on the public radio show “Studio 360” with Kurt Andersen to discuss the design of the Cleveland Indians' baseball stadium. Dwell turns to him for design book recommendations, Fast Company culls his opinions on corporate branding, and he is the resident design expert for articles in the New York Times. Debbie Millman has called him a “design personality.” In Graphis, Michael Kaplan called him a “design generalist.”

But it is as a “design observer,” more specifically as a founder of the online design journal Design Observer, which has garnered him a different kind of design audience. Here, Bierut can lure the likes of William Goldman and Stanley Kubrick into the realms of collaboration and typography, respectively. He effectively blends music and design when he pens a remembrance of the soul singer Wilson Pickett. He seamlessly, coherently, weaves references from Pulp Fiction to Napoleon Dynamite into the very fabric of design debate, somehow making the whole thing more relevant, more accessible—more fun.

Paula Scher, Bierut's partner at Pentagram since 1991, says this grasp of pop culture is evidence of even greater talent. “Michael has a brain that is a giant compendium,” Scher says. “He absorbs and retains everything and pulls it out at the appropriate moment and uses it to its maximal effect. Mention a movie and he quotes from it, maybe he enacts a little scene. Mention a book and he recites a passage and relates it to three other books that have the same spirit, that you haven't read, but you will now. Mention a designer or architect and he knows the most recent project they've completed and their first project, how they've changed, how they haven't, who influenced them, who they influence, and he sometimes will make a little sketch or diagram of their work. There isn't a day that goes by when I haven't asked Michael what he knows about anything and what he thinks about everything. If knowledge is power, then Michael Bierut is the most powerful person in the entire design community.”

In an essay on Design Observer, Bierut explains that it took him half his career to realize design is really about the ability to make connections to other things. He cautions designers, young and old, to remember this above all else. “Not everything is design,” he writes. “But design is about everything. So do yourself a favor: be ready for anything.”

With Bierut as our lead vocalist, we are.