Recognized as the ultimate “designer’s designer,” merging imagination, intelligence, creativity and craftsmanship through incisive and enduring design.

One evening, when Stephen Doyle was in high school in Baltimore, the phone rang. A woman’s voice said, “You don’t know who I am, but I’m just calling to tell you that you are going to go to Cooper Union.” What is that? Doyle asked. “The best art school in the country,” the voice told him.

Thirty-six years after graduating from Cooper Union and embarking on a career that has brought him eminence many times over, he related this story from the offices of his design company, Doyle Partners—now a studio of ten—near Madison Square in New York. “I don’t know who called,” he says. “She had seen some of my paintings at an art show. I’ve got these angels that take care of me.”

Observing Doyle’s design—immaculate logos, sharply observed book covers, landscape works imbued with the gravitas of longevity—makes it hard to imagine that this man would twist his fate at the behest of an anonymous phone call. But look again: Effervescence, humor and warmth are mixed in with his elegance. You can see it in conventional projects like branding for Barnes & Noble and book design for Stephen Colbert, and in unconventional efforts like a kinetic skin for a new shark tank building at the New York Aquarium.

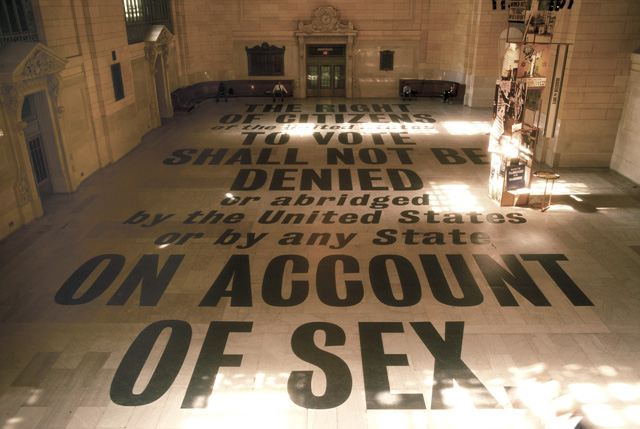

19th Amendment Installation at Grand Central Terminal, 1995 Client: New York State Division for Women; Design firm: Drenttel Doyle Partners; Creative director: Stephen Doyle.

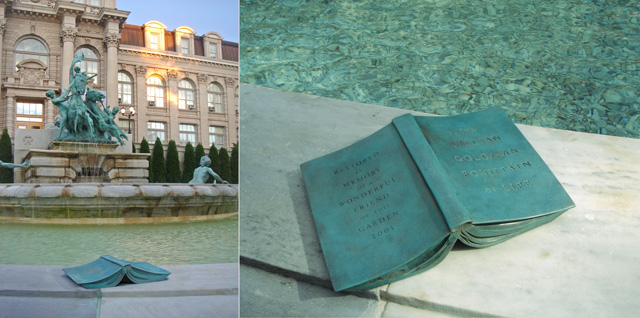

The Fountain of Life, bronze dedication plaque sculpture, 2006 Client: New York Botanical Garden; Design firm: Doyle Partners; Designer and sculptor: Stephen Doyle.

Truth, 2001 Client: The New York Times (op-ed); Design firm: Doyle Partners; Art director: Nicholas Blechman; Designer and photographer: Stephen Doyle.

The influences are not hard to trace. Chief among Doyle’s mentors at Cooper Union was George Sadek, a Czech émigré who appreciated what Doyle describes as “intelligent lunacy.” Another was Milton Glaser, who made ethical concerns the glue of his diverse design practice.

Doyle’s first job out of school was at Esquire magazine’s art department, which he followed with two years at Rolling Stone. Celebrated for its typography, Rolling Stone helped him develop a masterly way with letterforms that remains a hallmark of his design. In 1983, he joined the studio of another Eastern European who could fondly be described as an “intelligent lunatic”: Tibor Kalman, the founder of M&Co.

Doyle recalls his first few hours at M&Co. Kalman took the opportunity to fire the existing staff and tasked Doyle with filling the positions. In place of the rigidly trained Yale and Cranbrook grads Kalman decided weren’t advancing his interests, Doyle brought in talented school acquaintances, including Alexander Isley and Tom Kluepfel.

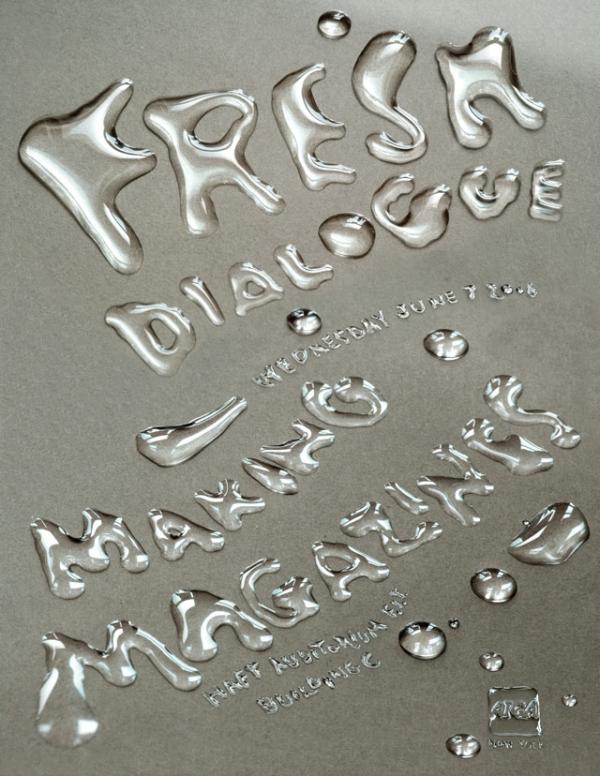

“Fresh Dialogue” poster, 2006 Client: AIGA; Design firm: Doyle Partners.

Cooper Union logo, 2008 Client: Cooper Union; Design firm: Doyle Partners; Designer: Jason Mannix.

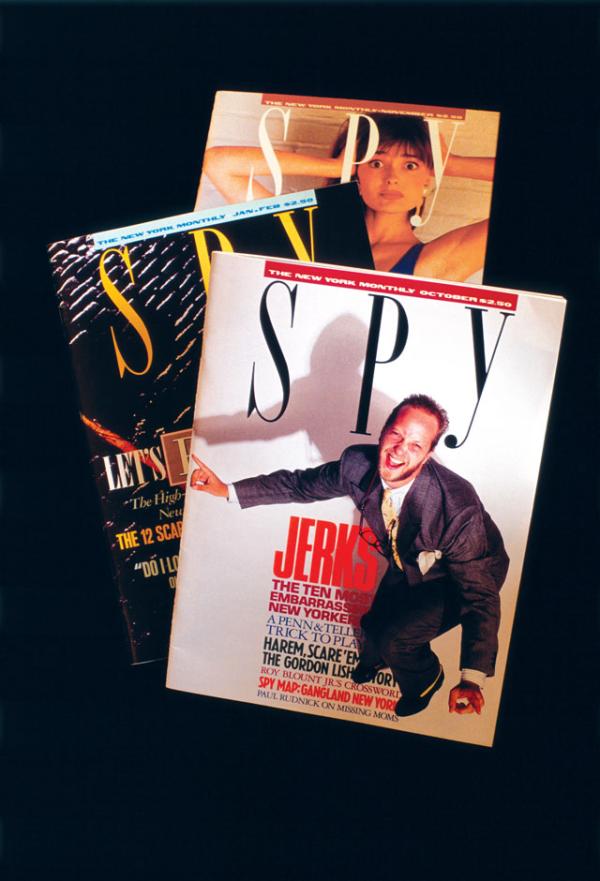

First issues of Spy magazine, 1986 Client: Spy magazine; Design firm: Drenttel Doyle Partners; Photographer (Chris Elliott image): Chris Callis.

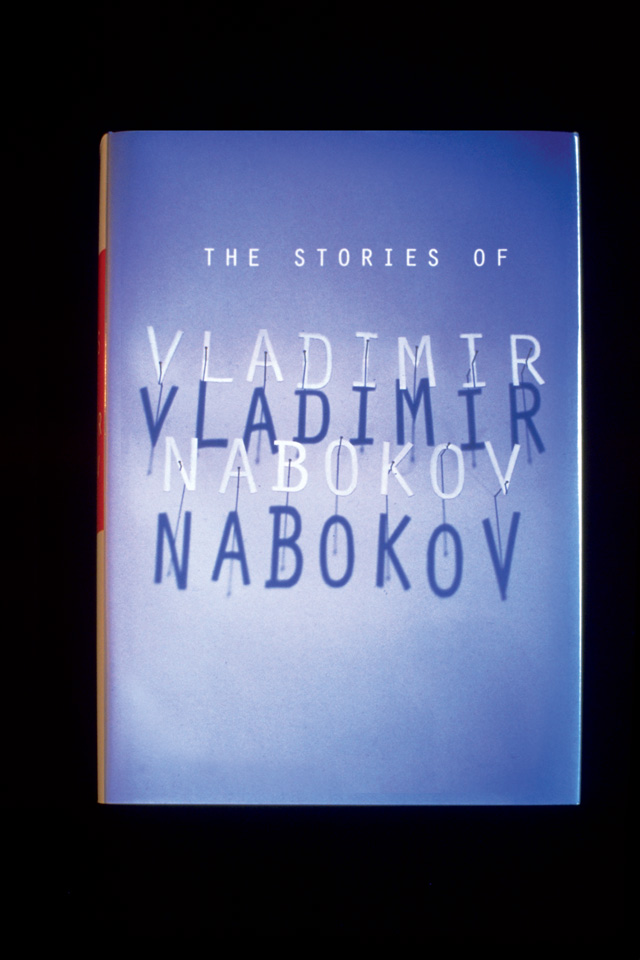

The Stories of Vladimir Nabokov book cover, 1995 Publisher: Knopf; Design firm: Drenttel Doyle Partners; Creative director and designer: Stephen Doyle; Art director (Knopf): Chip Kidd; Photographer: Geoff Spear.

Flailing in the stormy conditions of inexperience and then righting himself is a story Doyle tells repeatedly. He finds exhilaration in the terror, and something more: a fresh approach. In 1985, he risked leaving M&Co with Kluepfel to join William Drenttel in starting Drenttel Doyle Partners. The studio designed books, environmental graphics, identity systems and a celebrated prototype for a new humor magazine called Spy. When Drenttel departed in 1997, it became Doyle Partners. Among the studio’s many award-winning designs were the branding and product packaging for Martha Stewart Living Omnimedia, a project directed by Doyle’s wife, the 2014 AIGA Medalist Gael Towey. In 2010, he received the Cooper-Hewitt’s National Design Award for Communication.

Today, Doyle says that he loves his studio’s mix of video, sculpture, architectural projects and conventional graphics. Whether creating elaborate constructions for the New York Times and Wired, or developing an “indelible” baseball field for a park on the site of the former Yankee Stadium, or compiling classic movie clips into a witty video introducing an American Express conference on luxury publishing, or envisioning a new skin for Toronto’s First Canadian Place skyscraper, he both demonstrates and elicits delight. The word “jaded” does not appear to be in his vocabulary.

“There are fewer borders in design now, and that’s really fun,” Doyle says. “It just means there are only horizons. I have no nostalgia for the waxer.”