2016 AIGA Medalist: Gere Kavanaugh

Recognized as a pioneering multidisciplinary designer whose expert sense of color and style has enlivened everything from textile and type to interiors and exhibitions

Gere Kavanaugh has built a career that defies niches by tackling strikingly diverse assignments—from birthday cakes to textiles, park benches to vast corporate headquarters—and imbuing each commission with her trademark acuity for color, pattern, and whimsy. “I never wanted to be a niche designer,” Kavanaugh has said. “It’s like asking someone to eat hamburgers all their life.”

Kavanaugh’s varied output has dubbed her a designer of textiles, furniture, interiors, exhibitions, products, and graphics, as well as an artist and a color consultant. She’s also channeled a love of letterforms into type design, creating custom typefaces for the Nixon Presidential Library and Museum and Arklow Pottery in Ireland.

“I love too many things. I’ll design anything I can get my hands on—just ask me,” says Kavanaugh, an active designer at 86 years old, who’s itching for a commission to design a destination tea room or redo the interiors of an airline. “They’re just so boring!” she remarks with her usual affable candor.

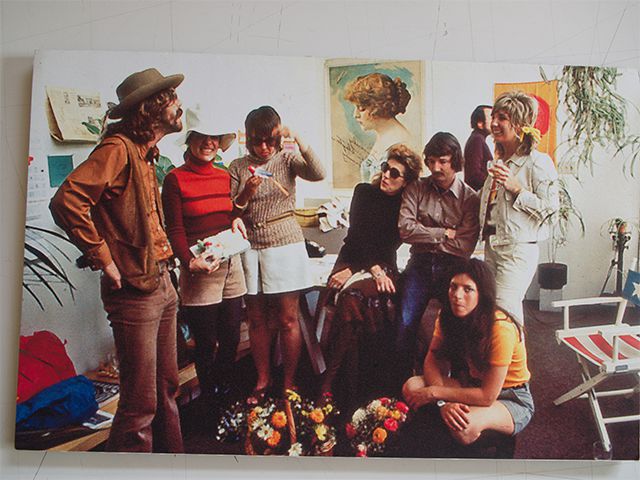

Gere Kavanaugh, center, from the forthcoming book “Gere Kavanaugh, Designer” (Metropolis Books, Fall 2016)

From the forthcoming book “Gere Kavanaugh, Designer” (Metropolis Books, Fall 2016)

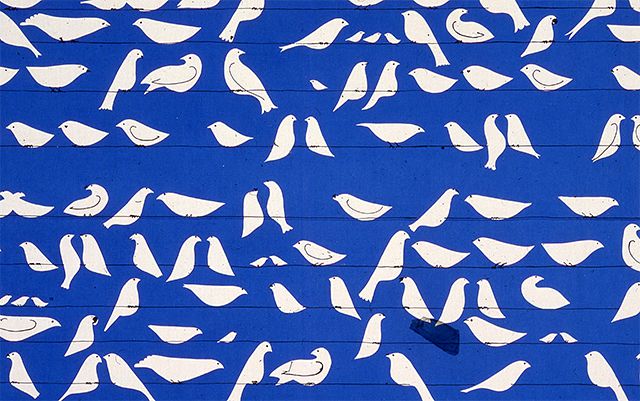

Textile design, from the forthcoming book “Gere Kavanaugh, Designer” (Metropolis Books, Fall 2016)

Kavanaugh’s prodigious and polymathic approach to design began in school. After studying fine arts at the Memphis College of Art, Kavanaugh went to Michigan to pursue a master’s degree at Cranbrook Academy of Art. There, she thrived in the tightly knit studio system, living and creating with fellow students working in ceramics, painting, textiles, graphics, and architecture.

At the time, both the classroom and the workplace were male-dominated, but Kavanaugh was not to be impeded by this fact. She was one of the first women to go through Cranbrook’s design program, along with mid-20th-century legends Ray Eames, Florence Knoll, and Ruth Adler Schnee. Cranbrook’s staff included strong male and female teachers, and Kavanaugh was encouraged by designers such as Finnish ceramicist Maija Grotell, architect/industrial designer Ted Luderowski, and textile designer Marianne Strengell.

After Cranbrook, Kavanaugh was immediately hired at General Motors. Buoyed by a wave of postwar optimism, Kavanaugh remembers this time as heady and exciting for designers, especially those working in Detroit. In addition to GM, design-forward companies such as Ford, Chrysler, Herman Miller, Eero Saarinen, and Minoru Yamasaki were all located in Detroit, then the center of design in America. “There was a milieu—an atmosphere—[where you felt] that by creating better products, you were creating a better world,” Kavanaugh recalls.

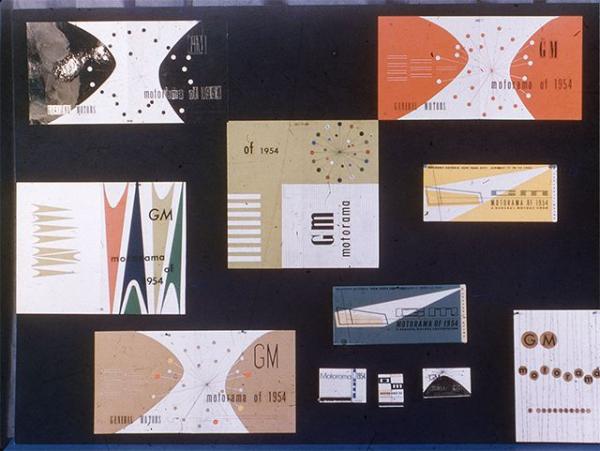

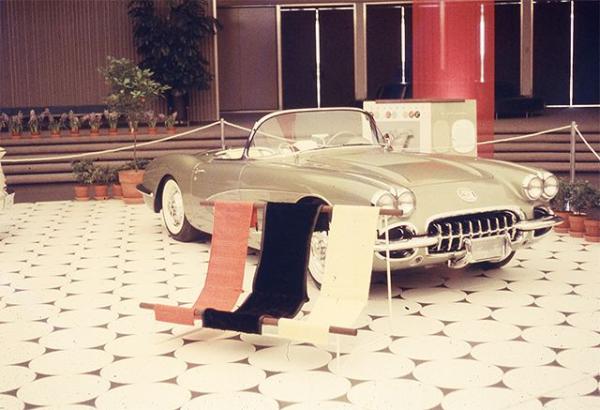

Kavanaugh worked at GM’s styling studio, equivalent to a company’s in-house design department today. She designed displays, created model kitchens, and would even, at times, work on the interior design of private homes of GM’s top executives. But as part of the design architecture group, Kavanaugh’s main focus was designing exhibitions to showcase GM’s automobiles. For one memorable springtime show, she rented 90 canaries and housed them in a trio of 30-foot, floor-to-ceiling columns made of Swiss cotton netting, which hung like transparent birdcages beneath the dome of the Eero Saarinen-designed GM Technical Center. “There were also lights underneath and when you turned them on, the birds would sing.” Kavanaugh likes to incorporate animals in many of her concepts, drawing from memories of living across from the Memphis Zoo as a child.

Print materials for GM”s Motorama automotive exhibition, 1954, from the forthcoming book “Gere Kavanaugh, Designer” (Metropolis Books, Fall 2016)

Furniture design, from the forthcoming book “Gere Kavanaugh, Designer” (Metropolis Books, Fall 2016)

Exhibition for GM’s Motorama automotive exhibition, from the forthcoming book “Gere Kavanaugh, Designer” (Metropolis Books, Fall 2016)

Model for exhibition design, from the forthcoming book “Gere Kavanaugh, Designer” (Metropolis Books, Fall 2016)

Kavanaugh was part of GM’s “Damsels of Design,” the first group of women to work as professional designers in a U.S. corporation, a move championed by GM’s legendary design director Harley Earl. The “damsel” moniker concocted by the company’s public relations department doesn’t always sit well with Kavanaugh, but she’s not interested in fueling the raging narrative about sexism and feminism. Her mindset is that of a humanist.

“She’s such a strong woman,” says graphic designer and GM archivist Susan Skarsgard, who interviewed Kavanaugh in 2013. “And although she’d deny she’s a feminist, I view her as somebody I really look to as being a role model for women and designers, especially those who work in corporate.”

In 1960, after four years at GM, Kavanaugh accepted a design position at Victor Gruen’s—known as the father of the shopping mall—architecture firm, first in Detroit, then in Los Angeles. Kavanaugh flourished in Southern California’s creative climate and enjoyed great freedom in her new role, working on interiors of retail stores and shopping centers across the country. Following Gruen’s vision of recreating the atmosphere of European town centers in suburban America, Kavanaugh designed the first town clocks at shopping malls as public meeting places.

She also forged a lifelong friendship with her colleague Frank Gehry, a relationship that led her to venture out on her own. Gehry and his design partner, Greg Walsh, invited Kavanaugh to split the $76 per month rent for a bungalow in Santa Monica that was so small they used the bathtub as storage for their drawings. After moving to a bigger space years later, the Frank-Gere-Greg trifecta was joined by Deborah Sussman (2004 AIGA Medalist) and Don Chadwick, best known as the co-creator of the iconic Herman Miller Aeron chair.

With the support of her colleagues and champions, the “unique, multi-dimensional design firm” Gere Kavanaugh Designs excelled. Her client roster has grown to include Pepsi, Hallmark, Neutrogena, Max Factor, and Isabel Scott Fabrics, who hired her to help set up an ikat silk weaving factory in South Korea.

Working with the patio furniture company Terra in the 1970s, Kavanagh invented the now ubiquitous market umbrella, at times referred to as the “California umbrella,” a design she was unable to patent because it had “no unique patentable parts,” she explains. Frustrating dalliances with patents and copyrights throughout her career have informed her efforts to help Cranbrook establish an alumni product archive, a place for alums to donate a design or artwork that companies can reproduce and pay royalties directly to the school.

Reflecting on how design students have changed since she was in school, Kavanaugh observes, “We’re living in the most exciting age that we can ever live in and have more disciplines to draw upon to produce our work. But you have to be smart enough to figure out the best tool to produce what you’re thinking. And this the students are not doing today.” She’s talking about using one’s hands for more than clicking around a computer’s track pad.

For Kavanaugh, her hands are still the best creative tools she owns—as they’ve been since she started doodling as a child. “Working with your hands teaches you about your inside person,” she says.

At the end of a lecture she gave at the Carnegie Mellon University School of Design in 2012, Kavanaugh shared some timeless advice for any student of design. “Have curiosity, and experience as much as you can, and look!” she exclaimed. “Every day you should be looking. You should be looking at how things are put together.”