Recognition

2016 AIGA Medal

Born

1938, New York City, New York

By James Gaddy

September 5, 2016

Recognized for her visionary work as an art director, for fostering emerging creative talent, and for her commitment to bridging the gap between art and commerce through design.

As co-art director of Harper’s Bazaar in the ’60s, art director of The New York Times Magazine in the ’70s, and creative director overseeing the reinvention of Vanity Fair in the ’80s, Ruth Ansel not only injected the glossy publishing industry with some rock ‘n’ roll flair, she showed us how magazines, at their best, are a vital visual record, a time stamp for an entire age. “Magazines give you an idea of what it was like to be alive at a certain time,” she says.

Ansel developed a seemingly simple formula for success: work with the best people, carve out room for white space, and then get out of the way. At Bazaar she worked with Andy Warhol and with Richard Avedon from the ’60s until his death in 2004. The ’60s also saw her side by side with photographers Melvin Sokolsky, Hiro, and Diane Arbus; in the ’70s, Sebastião Salgado, Bill King, and illustrators Roger Law and Ed Sorel; then Annie Leibovitz, Herb Ritts, and Bruce Weber in the ’80s; and Tim Walker in 2012 and onward.

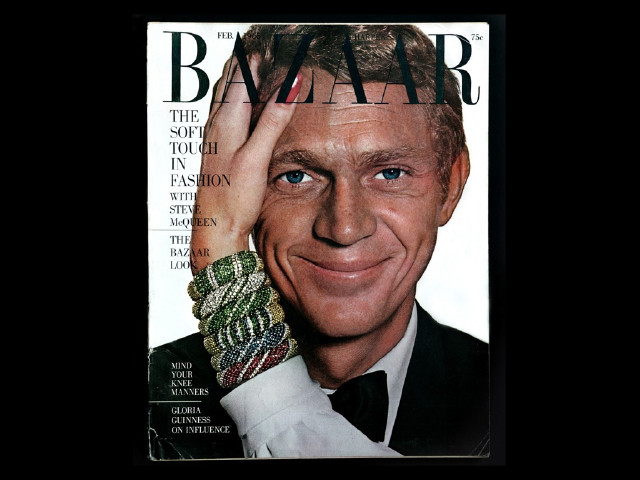

Cover of “Harper’s Bazaar,” February 1965, the first time a full portrait of a man made the cover. Photograph by Richard Avedon; art direction by Ruth Ansel and Bea Feitler; design by Ruth Ansel.

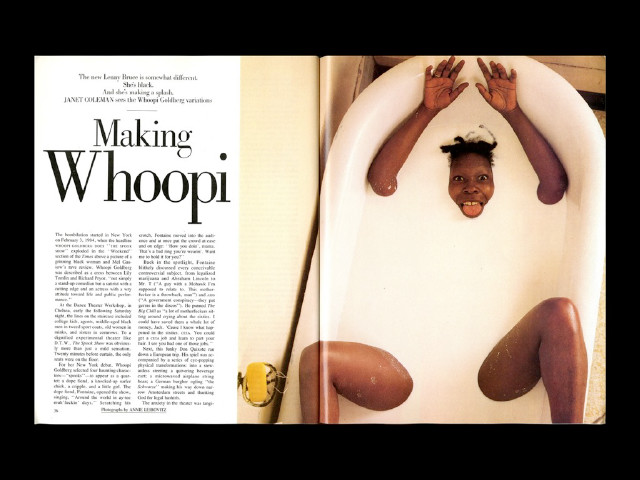

Interior spread of “Whoopi!” in “Vanity Fair,” June 1984. Photograph by Annie Liebovitz; art direction and design by Ruth Ansel.

Photograph of Fred Ota, Tom Miller, John Weber, 1953. Thomas H. E. Miller Design Papers, Special Collections and Archives, University of Illinois at Chicago.

Growing up in the Bronx, what Ansel loved best were the movies: The Thief of Bagdad, The Red Shoes. After graduating from Alfred University in Western New York with a BFA in ceramic design, she moved to New York City and began working for Columbia Records under Bob Cato. She fell in love with and married designer Bob Gill, who introduced her to what she calls the real “New York Design Mafia”—George Lois (1996 AIGA Medalist), Robert Brownjohn (2002 AIGA Medalist), Saul Bass (1981 AIGA Medalist), and Ivan Chermayeff (1979 AIGA Medalist). Their love didn’t last though, and she left to travel through Europe.

In 1961, Ansel moved back to New York City with the goal of working for Henry Wolf (1976 AIGA Medalist), who by then had succeeded Alexey Brodovitch (1987 AIGA Medalist) at Harper’s Bazaar. “Magazines were the closest thing I could find to films,” she said. But instead of Wolf she found the magazine’s newly appointed art director, Marvin Israel. “Walking through the doors of Harper’s Bazaar in 1961 with my portfolio under my arm was a life-changing moment,” she says. He hired her, even though she had no experience. “He liked that I didn’t have to unlearn any graphic design clichés.”

Another example of a foldout cover of “Harper’s Bazaar,” September 1968. Photograph by Hiro in New York; art direction by Ruth Ansel and Bea Feitler; design by Ruth Ansel.

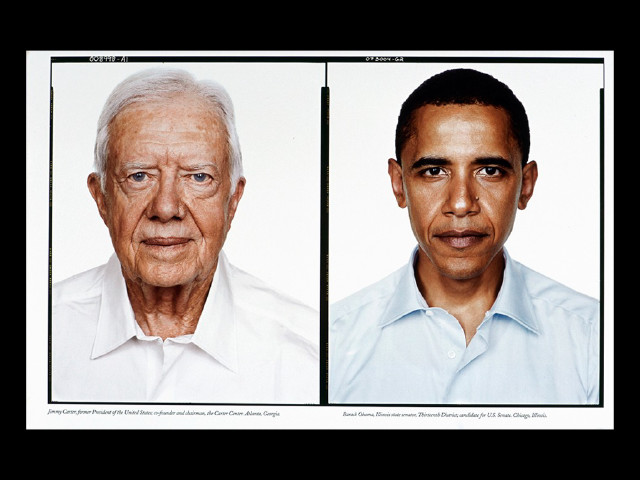

“Democracy 2004,” photo portfolio in “The New Yorker,” October 25, 2004. Photographs by Richard Avedon in New York; art direction and design by Ruth Ansel.

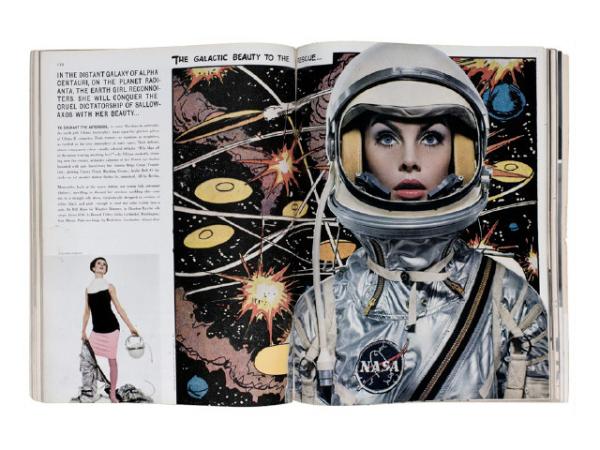

Interior spread of “Harper’s Bazaar,” April 1965. Photograph by Richard Avedon; art direction by Ruth Ansel and Bea Feitler; design by Ruth Ansel.

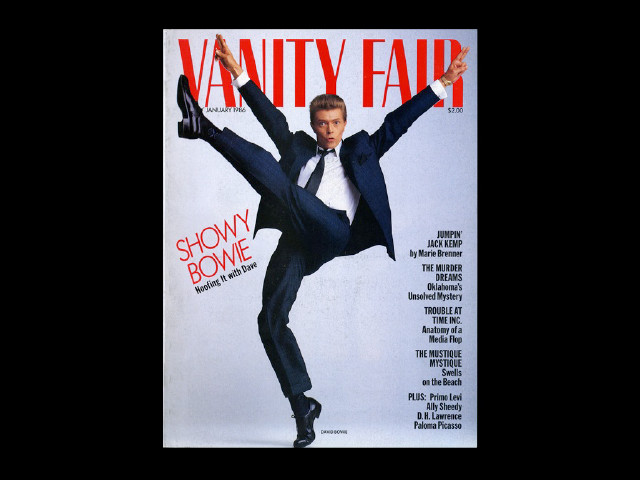

Cover of “Vanity Fair,” January 1986. Photograph by Annie Leibovitz; art direction and design by Ruth Ansel.

At Bazaar, she buried herself in back issues, where the work of photographers such as Henri Cartier-Bresson, Lisette Model, Herbert Matter (1983 AIGA Medalist), and A. M. Cassandre had been published. And she learned how to develop a critical eye—“to be curious seven days a week,” she says. “And I learned that brilliant ideas without the ability to execute those ideas brilliantly are not enough.” She was also a child of the moment: The Beatles, The Rolling Stones, pop art, street fashion. Israel encouraged that tension in the pages of the magazine. “With Marvin, the whole point of Bazaar was that you never just ran a beautiful portfolio of extraordinarily beautiful women who’ve been excessively retouched,” Ansel told The New Yorker in 2011. “You also ran a Diane Arbus portfolio of eccentric people who tattooed their body and lived on the Bowery, to have a counterbalance.” When Israel was fired two years later, she and Bea Feitler (1989 AIGA Medalist) became co-art directors; they were both in their 20s.

Their ideal woman was always in motion. “A dark, intelligent, introverted, beautiful woman,” as Avedon described in an article for Graphis. They refused to accept the usual boundaries and treated fashion with the reverence of fine art, even though most people at the time didn’t think that fashion photography belonged in a museum, or that a magazine could be just as important as a Balanchine ballet.

“For nine years they forged a revolutionary new direction for the magazine, mixing conceptual photography with pop art, street fashion, rock music, and film,” wrote Dennis Freedman, the founding creative director of W magazine and later the creative director of Barneys New York. “The new talent they brought to Bazaar changed the face of fashion photography.”

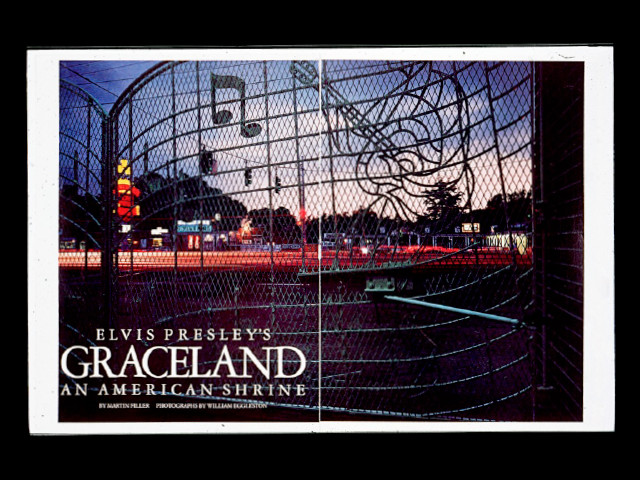

Feitler left Bazaar in 1969, and in 1974 Ansel went to The New York Times Magazine, where she published photographs by Gilles Peress, whose images from the streets of Iran appeared to be in conversation with political silkscreens by Andy Warhol. Then, in 1983, she revamped House & Garden, calling on photographer William Eggleston to create a series on Graceland. In 1984, she joined Vanity Fair as art director just as Tina Brown was taking over as editor and revitalized the magazine, creating a living record of the Hollywood-obsessed, go-go 1980s, as seen through the lens of Herb Ritts, Bruce Weber, and Annie Leibovitz.

In the early 1990s, she formed her own studio, designing monographs for Leibovitz, Richard Avedon, and Peter Beard as well as campaigns for Versace, Karl Lagerfeld, and Club Monaco. She also began a highly productive collaboration with the photographer Tim Walker and designed the wall graphics for a 2012 London exhibition organized around the publication of his book, Storyteller, that she also designed. “I believe in simple design that appears effortless, but it takes a lot of work to achieve,” Ansel says. “People are no longer aware [of] and impressed with how difficult it is to take a great picture... one that sticks in our minds forever. Anyone can take a good picture now and then. But it is very hard to make great pictures with intention, consistency, and originality.”

Though she’s never formalized a grand theory of magazine design, there are four rules by which Ansel abides:

Provoke: “Something new is off-putting,” she says. “The first human instinct is to reject it. A talented design director or photographer has to keep looking for it.”

Inform: A good and critical eye is more than picking fonts and grids. It’s about being sensitive to social changes and then bringing those observations to your work. “It’s a conscious act to change and evolve your thinking,” she says.

Entertain: “You’re always trying to create a magazine that’s as much about style and substance as it is about unexpected juxtapositions,” she says. “It’s up to the art director to encourage, surprise, shock, and have their finger on the pulse of the next thing.”

Inspire: Sometimes, she says, you have to get out of the way and encourage “a general sense of direction to those talented people you have the opportunity to discover, nurture, and offer a place for them to show their best selves.”

There are risks with this approach. To reject the average in favor of the potentially genius means sometimes being wrong—which is okay, she says. “Magazines are always a work in progress. Finding out what doesn’t work isn’t failure—it’s a way of eventually finding out what does work.”