Recognition

2018 AIGA Medal

Born

1899, Topeka, Kansas

Deceased

1979, Nashville, Tennessee

By Antonio Alcala

September 3, 2018

Recognized for pioneering a visual language as a graphic designer, artist, and educator who authentically celebrated the Black experience during the Harlem Renaissance.

Former President Barack Obama and First Lady Michelle Obama recently unveiled their official portraits at the Smithsonian National Portrait Gallery. Painted by Kehinde Wiley and Amy Sherald, the works present confident subjects with symbolic references and challenges to conventional views of power. They represent the best of American contemporary art and a nation where Blackness can be celebrated—one that Aaron Douglas was instrumental in helping to realize.

In 1925, Douglas wrote to Langston Hughes of his goal “to conceive, develop, [and] establish an art era. Not white art painted black… [But to paint] the very souls of our people.” Through the art, illustration, and graphic design he created between arriving in Harlem in 1925 and the beginning of his teaching career at Fisk University, he transformed the way Black people were depicted in print.

Douglas grew up in Kansas, in a home where his artistic interests and education were highly encouraged. Outside his community, however, existing political and economic structures of the early 1920s worked to limit most young Black men. Fiercely determined to succeed, he overcame these obstacles with a sequence of manual labor jobs, military training, and a self-funded college education. Along with his artistic practice, he read articles by W.E.B. Du Bois, Alain Locke, and Charles S. Johnson, developing a racial consciousness. Unfortunately, few artists in Kansas City shared this same interest. So at the age of 26, he left his job as a high school art teacher and traveled to Harlem in search of a community that might reflect and respond to his same concerns about Black life in America.

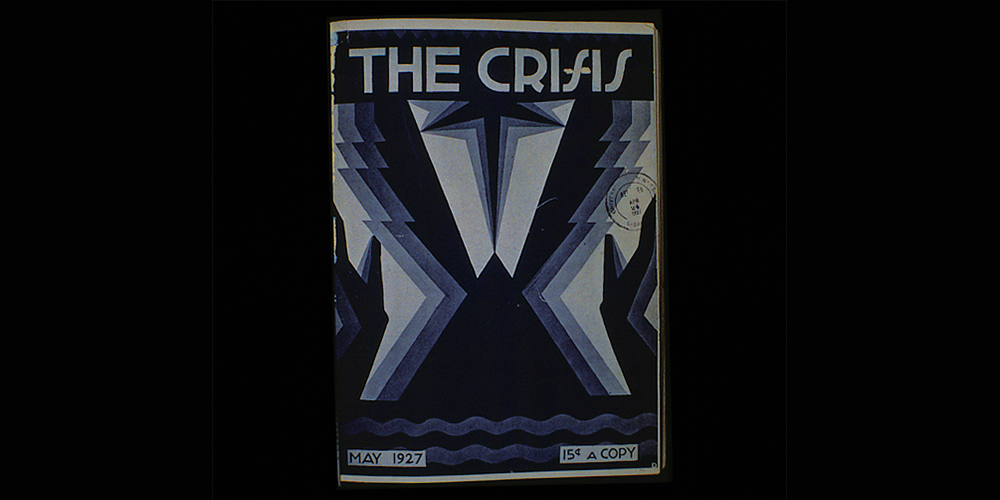

Cover of The Crisis, May 1927.

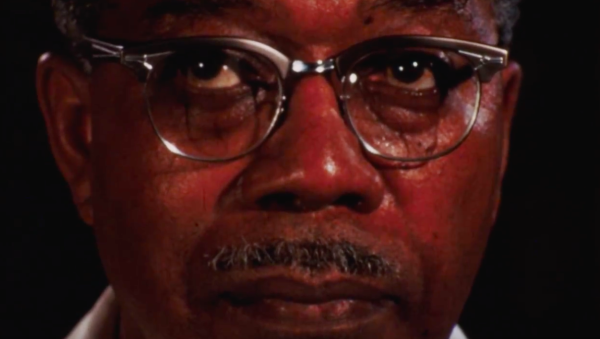

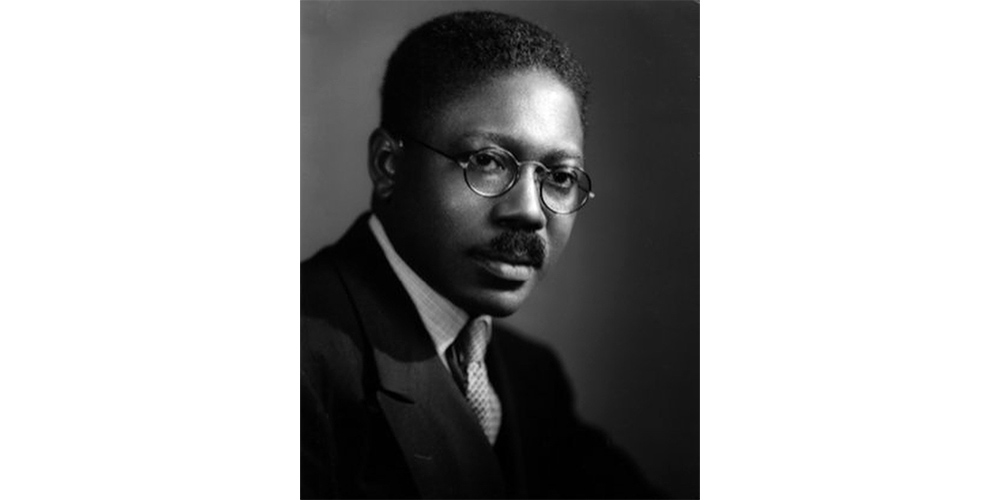

Aaron Douglas portrait.

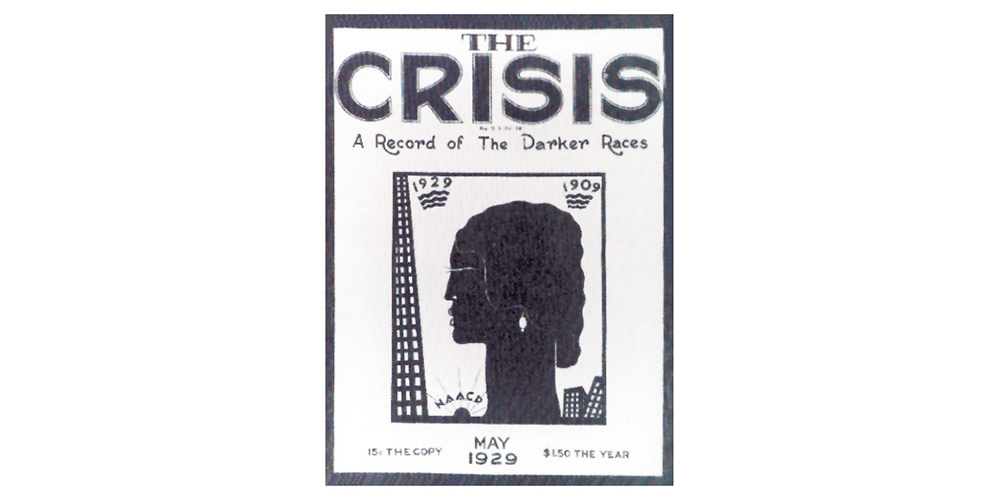

Cover of The Crisis: A Record of the Darker Races, May 1929.

In 1920s and ’30s Harlem, Douglas immersed himself in an environment where Black awareness drove the cultural experience. “There are so many things that I had seen for the first time… One was that of seeing a big city that was entirely black,” recalled Douglas in a 1971 interview at Fisk. “The fact that black people were in charge of things and here was a black city… eventually to be the center for the great in American culture.” This environment, replete with ambitious and creative writers, thinkers, and artists, proved immensely inspirational. In Harlem, Douglas dedicated himself to creating a new visual language that reflected the rich heritage of Black Americans.

Douglas’ new visual aesthetic evolved from deeply held beliefs combined with wide-ranging influences and disparate sources. He synthesized cubism, modernism, early art deco, traditional Egyptian imagery, and other African themes to create an artistic language that was meaningful and new. With this vision, Douglas succeeded in purposely avoiding caricatures and stereotypes commonly used in commercial artwork, while also distancing his work from European traditions by rejecting the use of a standard linear perspective.

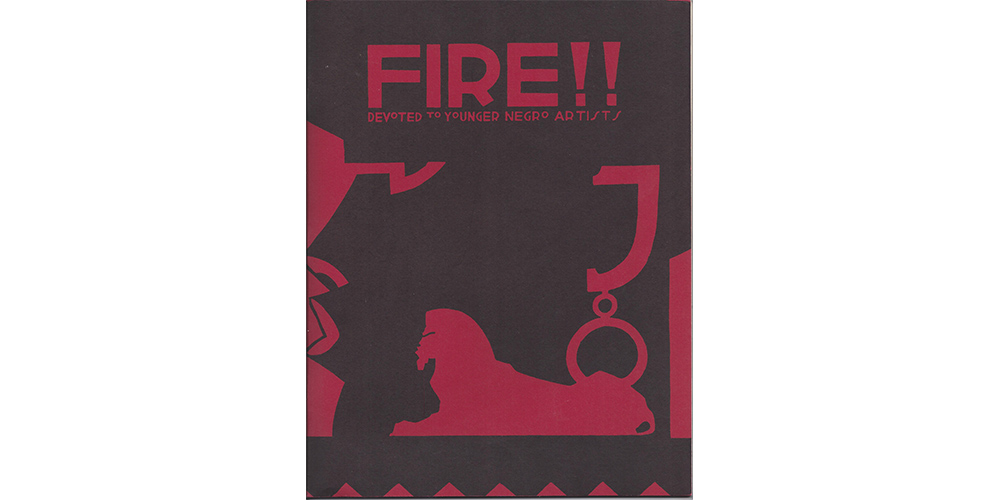

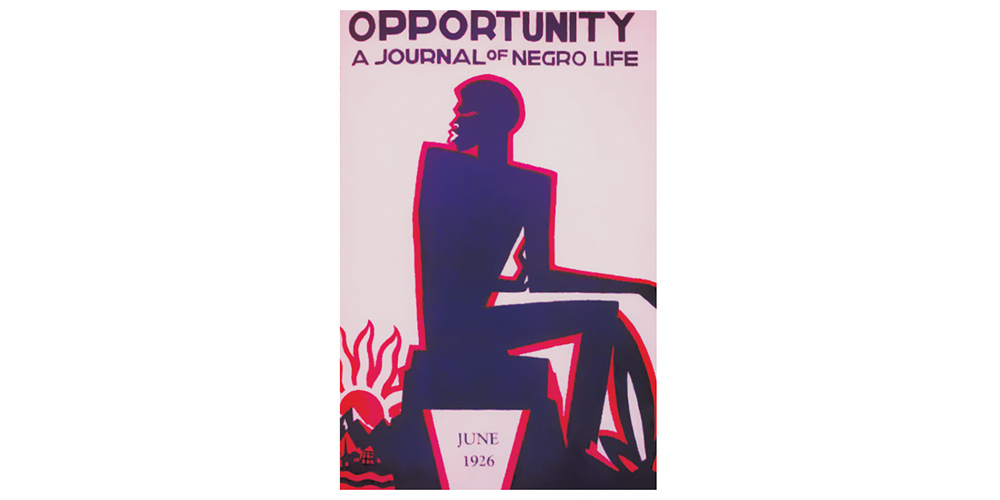

The most notable characteristic of Douglas’ style is a flat, one-dimensional scene rendered using silhouetted figures. People were created from simplified shapes, invoking ancient Egyptian forms with heads in profile but torsos facing the viewer. Reductive images also suggest a modernist-inspired language where a few pieces are used to represent the whole. In his cover design for James Weldon Johnson’s The Autobiography of an Ex-Colored Man, plain geometric high-rise buildings and flat smokestacks represent urban life and industry. In issues of Opportunity and Fire!! from 1926, pyramids, a sphinxlike lion, and lush plant-leaf silhouettes reference Africa. Douglas’ method moved away from traditional realism and toward a more symbolic representation.

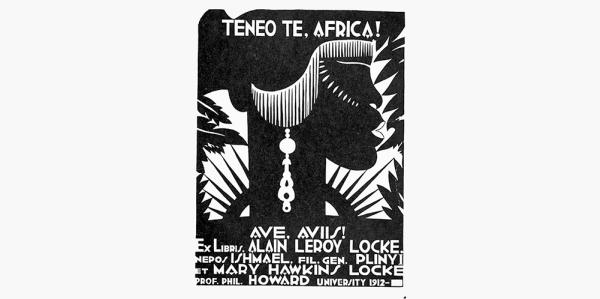

Bookplate for Alain Locke's The New Negro: An Interpretation, courtesy of the Moorland-Spingarn Research Center, Howard University Archives.

Cover of the first (and only) issue of Fire!!, November 1926. Magazine reproduced by The Fire!! Press, Elizabeth, New Jersey.

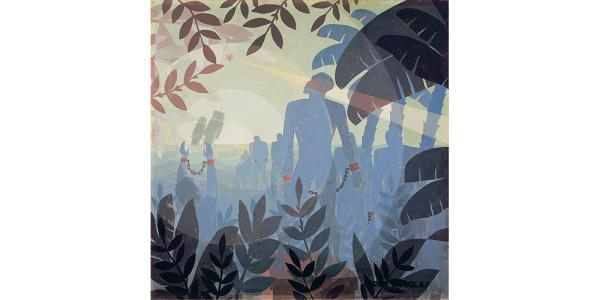

Panel from Aspects of Negro Life mural, 1934, created for the 135th Street branch of the New York Public Library.

Cover of Opportunity, June 1926.

His introduction of this new approach to depicting Black life and subject matter was immediately embraced. His silhouetted tableaux, almost always printed in black ink, became a visual fixture during the height of the Harlem Renaissance. They graced cover designs and interiors of important magazines writing about the Black experience in America, including Opportunity, an academic journal published by the National Urban League, and The Crisis, the NAACP’s publication. Similar artworks were featured on posters and book jackets for notable authors Langston Hughes, James Weldon Johnson, and Wallace Thurman, announcing the beauty of Blackness to viewers nationwide. By the 1930s, Douglas was widely recognized as the artist of the Harlem Renaissance.

In 1937, Douglas accepted a teaching position at Fisk University in Nashville, Tennessee. Moving from the heart of Harlem to a historically Black college in the segregated South was a monumental shift. The change, however, brought new opportunities to promote his vision of the Black voice in art, and allowed Douglas to focus his time and energies on painting and teaching.

Douglas founded the Fisk art department and served as its director for 29 years. On campus, he painted a set of murals presenting a history of Black people in the New World that remain in place to this day. In 1949, he helped establish the school’s Carl Van Vechten Gallery, with the accession of The Alfred Steiglitz Collection, including 100 works by masters such as Cezanne, Picasso, Renoir, O’Keefe, and Steiglitz. His efforts helped provide a powerful teaching tool in the segregated South that still resonates today. “Aaron Douglas was one of the most accomplished of the interpreters of our institutions and cultural values,” said former Fisk President Walter Leonard. “He captured the strength and quickness of the young, he translated the memories of the old, and he projected the determination of the inspired and courageous.”

In the classroom, Douglas emphasized an understanding of art history and encouraged students to develop an awareness of Black history. He taught a generation of young Black artists how to give form to their experiences, making them real for themselves and others. His leadership helped shape a growing artistic community that embraced and promoted Blackness as a subject. The hundreds of students Douglas mentored in turn became artists, teachers, collectors, and creators, teaching others through their own work. In doing so, they undoubtedly helped shape a culture and attitude where today, artists like Kehinde Wiley and Amy Sherald can be recognized and praised for the importance of their subject matter and the excellence of their artistic practice.

We’re forever grateful to Douglas for his artistic and moral leadership, and for providing a creative compass for designers striving to represent everyone’s story. He was a pioneer who formed a new milestone in the history of American commercial art—the moment when he presented to the world an authentic Black voice to represent Black creativity and experience with beauty and elegance.

Sources

Aaron Douglas: Teacher Resource. The Spencer Museum of Art, The University of Kansas, 2007. http://www.aarondouglas.ku.edu/resources/teacher_resource.pdf

Washington, Michele. “Aaron Douglas’s Design Journey.” AIGA, September 1, 2008. https://www.aiga.org/design-journeys-aaron-douglas